Last week I discussed the pros and cons of hiring a professional editor for your novel manuscript, and my personal experience in choosing one for myself. This week I’ll show you what you can expect from different kinds of editing services.

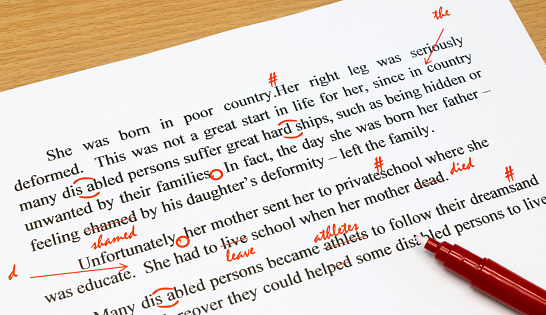

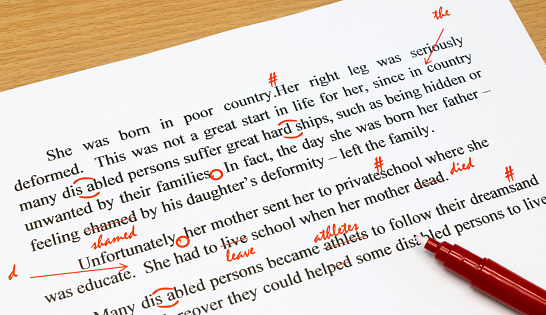

The muses aligned or the planets favored us (or insert your own supernatural reason) and the same day we hired a professional editor for my daughter’s and my middle grade manuscript, we won a free first ten pages critique through a contest. In this case, the critique came from a past winner of #PitchWars, who had a manuscript good enough to be chosen by a mentor and who then went through the intense revision process that is the hallmark of that event. So while he is not strictly an editing professional, he is certainly an experienced one. And, because it was through a contest and not a manuscript swap between peers, he was not looking for reciprocation the way a fellow writer in a critique group might. Because this critique only covered 10 total pages, the comments drilled down to word level. This is the kind of critique you may get with a Copy Edit. Below is a screen grab from the middle of those ten pages, with comments from my editor:

In this case my editor requested the pages in a Word document, in proper manuscript format. This works well, because the comments and edits can be tracked, as you see above. Others prefer the online Google Docs, which have similar tools, however with Google Docs, you can see the edits live as they come in, and respond with comments and questions of your own. A third option, Dropbox, is the best of both worlds, as you can share a link to a Word document in your Dropbox, and your editor can open that same document in his or her Dropbox. This arrangement also allows for instant gratification and back-and-forth. I prefer the Dropbox method, because ultimately the manuscript is going to need to be in Word, and I don’t want to have to copy and reformat the whole thing if I don’t have to. But any of these methods will get the job done.

For the professional edit I chose a developmental editor, because our manuscript was well polished from a grammar and spelling standpoint, and it had already been read by scores of beta readers and critique partners, so I was confident the vast majority of the typos were cleaned up. Likewise, I felt confident that line-by-line issues, such as awkward transitions, confusing sentences, and inconsistencies had been resolved. What I paid for was a Developmental Edit, which covers plot, structure, character, pacing, dialogue, world-building and writing style, presented in an overall critique letter, rather than line-by-line or even chapter-by-chapter breakdowns.

I chose Write On Editing, for their experience, their age-group focus, and their reasonable price. I was ultimately won over by their fast and friendly replies and willingness to answer questions. In fact, before asking for a dime, Michelle invited us to send her the whole manuscript so she could read it and tell us which level of editing would be the best fit for us. She recommended the least expensive option, and even worked with us on the price. Here are some of the comments we received after about two weeks:

Plot:

You have a wonderful story line in THE LAST PRINCESS…. (a full paragraph detailing the things that Michelle liked and what worked).

There are a few points that I feel you might want to address however.

Cat seems to immediately accept that she will become the next princess without too much internal examination or obsessing about what that means for her, her future, or her family. A bit more internal dialogue would help readers to connect with that new-found responsibility. Also, what is Cat expecting to actually do as a Princess? She makes vague statements about wanting to unify the fae but what does that actually entail?

Cat’s time at Squirrel Scout camp is so much fun! The pranks were pretty funny and it was a great way for her to meet Hunter and learn new skills too. That said, pranking usually goes both ways at camp. Can her group plot or even prank other groups in what they think is retaliation? I would imagine these girls would be speculating nonstop about who was messing with them, but that line of thought seems pretty non-existent.

World Building:

Much as I like the plot, I feel like this is one of the weakest areas in THE LAST PRINCESS. I honestly have no idea what time of year the story is taking place. At the start, Cat is working on home school projects but shortly afterwards she is going away to camp for a week. Is school just getting out before summer? Giving more details about the timing will help the reader to place themselves more firmly in the contexts of your character’s lives.

Another facet I wasn’t too sure on was the family’s booth at the Rockford Fair. While reading, I was distracted trying to figure out if it was located in a travelling or permanent fairground. I think it’s the latter, but if so, how does that work? Fairs typically last for a short period only. Consider changing it to a small shop in a tourist type town that might have a carnival aspect (I kept imaging Coney Island, to be honest). Think about what makes it unique or special and why people come to visit.

Character Development:

Cat’s Mom: One of my main concerns is the unevenness of this character. I like where she ends up, but I was quite confused with her character for most of the novel. Cat emphasizes the fact that her mom expects her to be “little miss perfect” by getting good grades and avoiding things like fairy tales but I didn’t see much beyond those two points. In fact, she has her join Squirrel Scouts which seems the opposite of being success-minded since they go hiking and get dirty etc. (unless you incorporate something how she thinks it will give her leadership skills or something). And it doesn’t really match with her actions either. I couldn’t understand how a mom who runs a booth selling flowers and pottery at a fair would be so preoccupied with perfection, as she seemed quite hippy-ish. You might be able to keep the details as is, but make the mom a bit more OCD regarding Cat’s activities. She already is concerned about school work but you could add in scenes of her carefully scheduling out Cat’s every minute between scouts, soccer, school, and helping with the shop, for example.

Michelle rounded out her critique letter with a number of random thoughts:

– How did Thomas get over the mumps so fast? Wouldn’t he be quite weak after leaving the hospital, yet their mother takes the family out to dinner that night.

– On p.77 Cat tells us why she thinks her family is more poor than usual. Instead of telling your reader all at once, could this be broken up and inserted in little snippets throughout so it gradually builds?

Finally, the editing package included a 45 minute Skype or phone conversation, where I can ask questions and get feedback on possible solutions to some of these issues. To get the most out of this, I’ve started a list of questions to ask, and will continue to add to it right up until the scheduled time for our call.

Next week I’ll discuss how I plan to make the most out of these critiques, and how several of the comments led to ideas on how to fix the issues.